Listen to the story, read by me. If you prefer…

For almost as long as he’s been alive, my son has loved being read to. When he was just able to walk, if a visitor came by the house and made the mistake of sitting down, he’d approach them with a book. Then up onto their lap he’d hop.

I’m not the type to read kids novels like Harry Potter or The Hunger Games. But as a parent I read kids literature all the time. Every day that I am with my kids. Which is damned-nearly every single day. Over eleven years and counting.

It’s fun reading to kids. With my son I dug out all the remaining copies of the Mr Men series my mother or I had salvaged from my childhood. Then again with his sister, who also branched out into the Little Miss books. He tells a very tight and funny tale, that Roger Hargeaves. (His son Adam, who picked up the family masthead, not so much.) A writer can learn a lot from the slim, original volumes of Mr Men. An illustrator, too. Particularly if you mostly have access to children’s markers.

On a trip to Bart’s Books in Ojai years ago I spotted a dog-eared copy of Roald Dahl’s Charlie and The Chocolate Factory and talked my son into giving it a try. He was off and running from there, and I’ve been lucky enough to re-read the whole Dahl catalog with him. His 7-year-old sister’s finally showing some interest, too. Mostly thanks to the two Matilda movies.

My daughter is having a hard time moving on to chapter books, though, still preferring less words and more pictures. This is frustrating me, the reader, and my urging her toward more substantial fare is frustrating her in turn. But by god, how long must a person suffer Seuss? It’s fun to begin with, but I’m at an age where things start to hurt for no reason. Excessive tongue-twisting could potentially result in long-term injuries.

Still, give me a children's book over a book written for adults with the intellect of a child, any day. The best kids books are written so perfectly that you can’t imagine them being a word longer or shorter. Goodnight Moon comes to mind. As well as more modern classics like The Gruffalo. The best are economical, with bold characters and just enough turns of the plot. They are weird, without being unrelatable, even to a child. The best are merciless, too (see: Dahl). Children are almost impossible to offend, so why worry?

I try to lose myself in the stories and enrapture my kids in the process, but they are born to a writer, so it doesn’t always go so well. Far be it for me to name names, but I have been known to throw books of poor quality down in disgust and vow never to read them again. The children are very understanding. My son loves to write, too, so he has taken to joining in these careful critiques. Deficiencies in plot, needless repetition, poor pacing, clunky prose.

One of the authors he most enjoys is churning out titles at an astonishing rate. Instead of ending dialogue with “he said” or “she answered”, this author likes to use more pithy and often downright stupid phrases, such as; “she put in” or “he offered”. It is a discredit to my own writing, perhaps, that I can’t adequately express how much those repeated usages infuriate me.

Between that, the fading story arcs and frequency with which this particular author’s titles appear on shelves, I was complaining to my wife recently about how obviously weak the books are becoming (even our son is losing faith). “I think he’s using ChatGPT to write them,” she replied (see, not so hard!), with a swagger about robot intervention only people who actually work for Big Tech tend to possess.

How did I not think of that? Of course he is using AI. Why wouldn’t he? Why wouldn’t anyone these days? That seems to be a universal question, that reaches far beyond writing, and like a lot of contemporary dilemmas, one I’m struggling to reconcile. Or even feel comfortable with. But this one – whether to write, or have words automatically assembled for you – strikes particularly close to my heart.

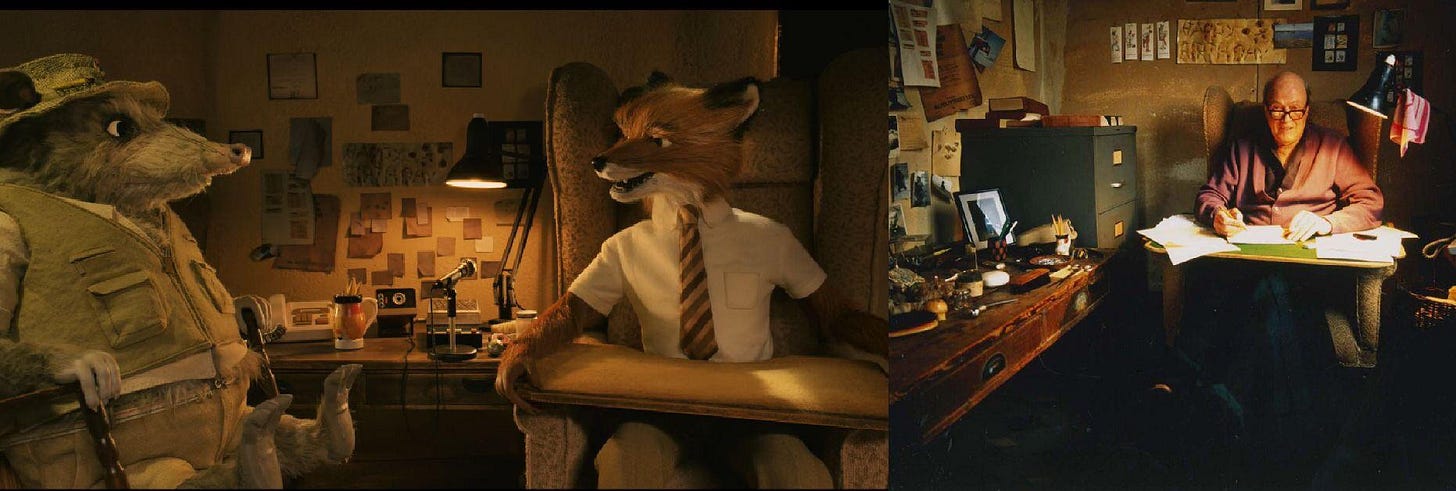

When I think about what it feels like to be a writer, fully engaged in their craft – embodying the whole life, as it were – I sometimes think about an old BBC TV special on Roald Dahl that my eldest brother sent me a clip of on YouTube once. In it Dahl gives the viewer a quick tour of his writing hut which I had heard about many years ago, when I was still reading his books for the first time, and about the sleeping bag he would wear up to his waist while working in winter. Now here he was, in grainy, square-formatted footage, showing us how he writes. In a hut that was his alone, at the back of the garden, cleaned only once, after a goat broke in and pooped on the floor, forcing him to finally sweep it out.

Dahl made himself a writing board to rest over his armchair, kept the pencil sharpener and thermos handy, always six pencils (exactly), and away he went. (You can see the arrangement mimicked, as homage, in the Wes Anderson film adaptation of Dahl’s Fantastic Mr Fox.) There he worked the whole story out longhand, on legal pads. Not even a typewriter, let alone ChatGPT. I don’t know about you, but I can feel that when I read. I want to feel that when I write, too. Even if it is on a laptop, upon a desk with a motor that can drive it up to standing-height at the push of a button.

Now my son is old enough that he likes to read these stories of mine, too. I have become a part of his reading (Hey, kid!), which is not something I ever really thought much about being. Or becoming. But I would never short-change him – or any of you – with ChatGPT. What would be the point?

Writing is an act of sharing. Deep sharing. To entertain is one thing, but why else do it? Most people who create art make little or no money from the act. Including millions of writers. A fact borne out by a quick look around Substack. Still we do it, either way. Some will use tools like ChatGPT to chase fame, or money, no doubt. To meet a deadline. Maybe it actually writes better than they can. But not most writers.

More so, it’s in the physical act of writing that so much of its unpredictable creativity is found. It’s a walk one goes on with their own mind, hoping to spot things along the way. To let a series of electronic chips take that walk for you saddens me beyond comprehension.

A lot of people will say, “Oh I just use it to get started”, or to “speed things up”. But I worry that I wouldn’t know where to stop, or which ideas were truly mine. Like when Seinfeld starts shaving his neck, doesn’t know where to draw the line and winds up shaving his whole chest. The internal debates of a writer are bad enough, do I need to introduce another cold, inanimate voice?

What of the readers, too? There’s a dishonesty in using AI to write, in my mind, that feels like it’s harming both parties. I remember that my son, before he could read, would insist on me or his mother naming the author when we began a new book. His sister loves to see author photographs on book jackets. She also asks me to read the name of the illustrator. Sometimes she will add, “Are they alive?” Like all of us, she is interested in who she is sharing the world with and what they have to say. What they have to offer. If they are dead, she can file them in a different part of her emotional library, but see that they left something of themselves.

I feel the same way. Rarely do I start a book without turning back to the page of legal details, just inside the cover, to see when it was first published. Where? In which language originally? How long has this person’s voice lasted? Long enough to now reside in me. Do I feel that way about computer servers? Does anyone?

Sam Altman, the founder of OpenAI, had a son this February. What will he read to his boy? I wonder. I doubt it will change his feelings about the technology he creates and so passionately evangelizes. But I doubt he thinks much about the creative process, either. About what it means to tell a story that isn’t for money. That isn’t little more than a “pitch”.

The image of Sam Altman reading a child an AI-generated bedtime story, the words falling awkwardly from his biomedically-maximized face, sits about as comfortably in my mind as that of the Tesla popcorn robot changing a child’s diaper. I can picture him asking his partner, “Why are we reading him stories, when I could just be teaching him to prompt?”

Between decades of bookstore closures, the disintegration of daily newspapers and the transformation of social media platforms into endless video feeds, it can feel very much like the written word is under assault from all sides. The direct implication being that the writers behind those words are pointless. Without value to their communities. Still, early-education experts continue to push all parents to read to your child! It feels neglectful – maybe even abusive – not to. So we develop these readers and writers, then what?

A lot of Harry Potter readers are feeling morally conflicted these days, like a part of their youth has been ripped away from them, given that the author has taken on some oddly passionate and aggressive points-of-view on transgender rights. It’s a feeling we’ve all had, especially in the past decade, as the public has looked more closely at the private lives of artists and artists have felt more compelled to share their thoughts on diverse topics.

Conversations about separating the “art from the artist” abound. Even when I was a kid, I remember my mother telling me that Dahl divorced his wife while she was ill, which made him far less cuddly a figure in my mind (in fact he’d been having an affair with his next wife for 11 years. What would Charlie Bucket think?). Later Dahl was accused of anti-semitism. It’s hard to imagine a person who has connected with you, brought you so much joy, being “bad” in some way.

Seuss was a racist, it’s alleged. Yet, no more than most of my generation’s grandparents, I’d wager. Mistakes are human, and I don’t just mean spelling and grammar. It’s how we respond to the feedback that counts. We’re all a bit “bad”. How else could people so evocatively write villains? Maybe that’s the appeal of AI-driven art for some, and the removal of authors from the experience. People are difficult. “Problematic” as we now say. Perhaps to the more tech-minded the solution is simple; no person, no problem. I saw a kid in a T-shirt on the street in Montana recently that read; People: One Star. Would not recommend. Catch me on a bad day and I might bump it down to zero stars. But do we really want to remove people from everything?

The sudden and growing popularity of home delivery anything and driverless taxis and chatbots and a thousand other tech-forward social trends that isolate us, might suggest that, yes, a lot of us do. AI is a perfect fit for these times of moral anxiety. A deeply partisan age of less and less human contact. Where we are each cast as “one of them”, based on politics, race, gender, sexuality, geography, sporting team… On the verge of a society in which we trust each other less than robots. Even that T-shirt is a nod to the practice of ranking Uber drivers, now under serious threat from autonomous Waymos.

Reading is one of the last ports of access we have to the real feelings of real humans. I hope we don’t squander that in the name of cash, convenience and the eradication of “awkward” human contact, too. Our kids are already under threat of being groomed into a person-less existence of tech-enabled consumerist totality. On screens from toddling age, “chatting” to friends rather than actually talking to them, gaming instead of playing. Sitting ducks for whatever new product or idea technology companies are being paid to shove down their naive throats, wrapped in glittering pixels.

Besides, the Twitter/X AI chatbot “Grok” went on a “problematic” racist tirade recently anyway. No fun story, dead author or esteemed literary career required. The least it could do is try to trump Cat In The Hat.