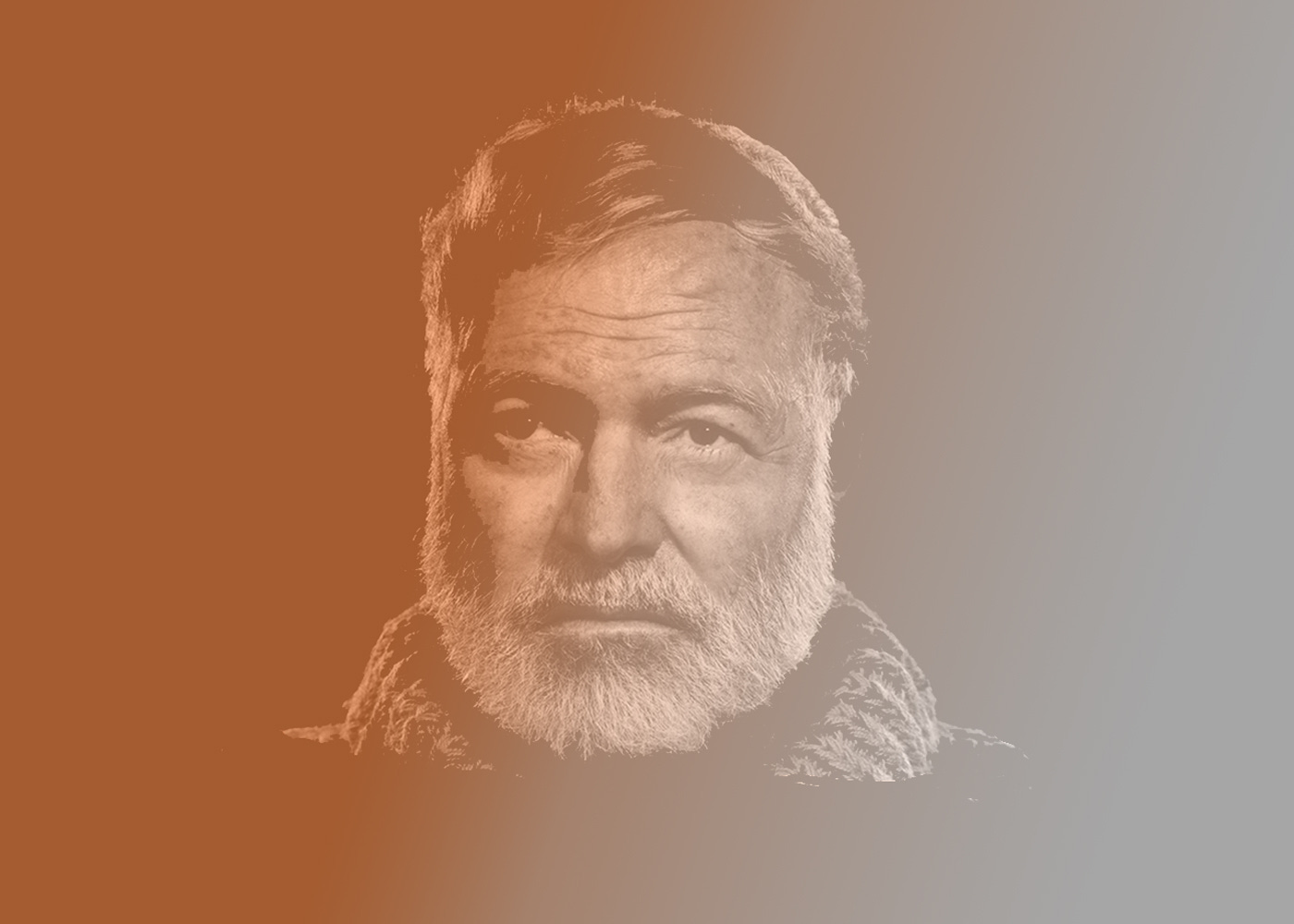

Poor Old Papa

The Hemingway lore lands heavy on the busted shoulders of this writer and father.

Listen to the story, read by me. If you prefer…

When our son was three I dislocated my shoulder for the first time. I ran and fell on wet pavement, trying to stop him from spraying me and his pregnant mother with a garden hose. By the time his sister was three, I had dislocated it twice more and finally scheduled shoulder reconstruction surgery.

I had put off surgery the first two times because surgeries are horrible and inevitably come with a prolonged period of debilitation. This is not a state of being that suits parenting. Particularly modern parenting, which is a full mind, body and soul endeavor. I sense mothers have always known that, but it’s news to a lot of newer dads. Of which I was one.

For the body, my main goal in recovery and rehabilitation was to still be able to throw, tackle, shoot a basketball and otherwise play with my kids. It would take many months of physical therapy, even after all the resting and healing, to reach that end. Early on, I remember being happy just to be able to sit at my desk and type again.

Those first post-op, medicated days in bed — icing pad almost always strapped to my shoulder, propped up on a special wedge pillow, needing help for most tasks — were slow and tedious. Even reading felt oddly laborious in that state, so I resorted to watching TV on my laptop. There I hoped to find not just distraction, but medicine for the mind, perhaps even the soul, while the body recovered.

Around that time Ken Burns released his three-part Ernest Hemingway documentary, with a total running time of almost six hours. I had never made it through a famously educational Burns mega-doc before. This seemed like a great opportunity, on a subject of obvious interest.

I adopted the name Hemingway as an adult, from my mother. There has never been a direct familial tie established to the famous writer, but still, with the name she thought I should know the work, and took it upon herself to gift me many of his books when I showed an aptitude for writing during my late-teens and early-twenties.

I still recall my first university writing teacher (the late, great poet Judith Rodruigez) assigning us Ernest’s short story “Hills Like White Elephants”. I’d never read anything quite like it. His economy of style — particularly when it came to barely expressing emotional motives or reactions — fit perfectly with my repressive, Catholic boys’ school upbringing. Here was unceremonious, muscular, quick-witted, dry writing. For real men.

By the time I came to Burns’ documentary, twenty-something years later — with two children running around the house, their dad bedridden and unable to even chip in for the time being — life, and my impressions of it, felt very different. I’ve always enjoyed Ernest’s work, but by then could more easily see the holes in his hyper-masculine narrative. Both on and off the page. Through the laptop (for once literally on my bed-ridden lap) they were about to be torn open even further.

Already in a vulnerable state post-surgery, the Burns documentary shocked and gradually upset me more and more. I could take or leave the short roster of largely boring and obvious “experts” but, through the film’s detailed biography, it was the raw exposing of Ernest’s myth that struck like an oar to the head.

Ernest was a wreck. Multiple concussions, through various misadventures; flagrant alcohol abuse; marital hopelessness on a world stage; a transphobe, who may very well have harbored his own gender-bending impulses; and, most impactful to me given my present stage of life, a terrible parent. He died by suicide at the age of 61.

A story I expected to be quite illuminating, maybe even inspiring, left me feeling incredibly sad.

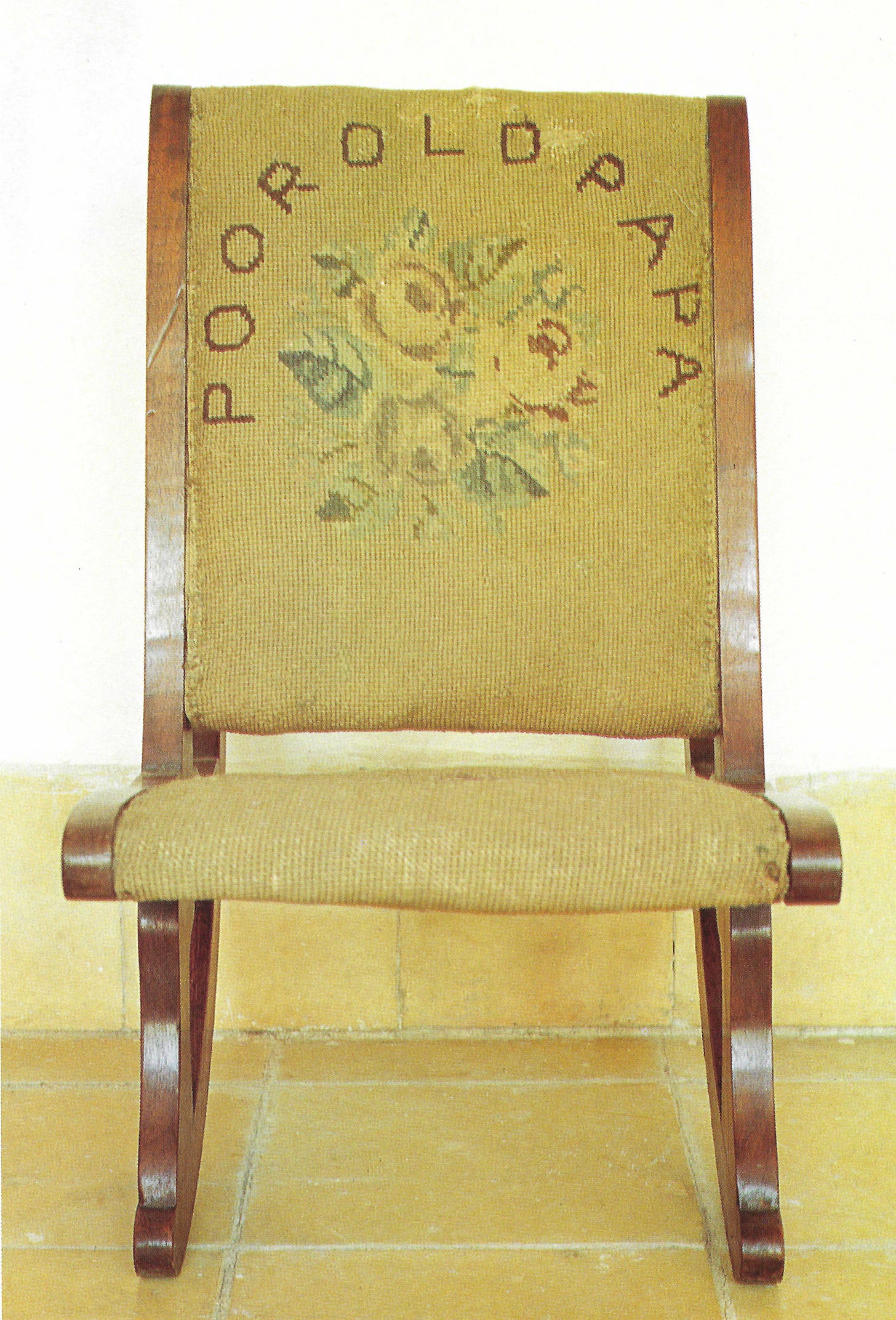

One of the Hemingway books my mother gave me once was an amateur photographic biography she purchased at his old home in Cuba. It’s called Poor Old Papa. An elaboration on the nickname, “Papa”, which Ernest gave himself. Long before he even had children, which seems odd.

I assume that like a lot of men I grew up around, becoming a father was seen as a life goal to Ernest, more than a calling or the complicated responsibility it often seems to me. A destination, rather than a journey. Something you simply labeled yourself (even without children), not grew into. A badge of honor. On par with a doting wife, solid career, a few sharp-cut suits and a bloody handsome golf swing.

Ernest’s second of four wives, Pauline Pfeiffer, gifted him a foot stool which still sits in his now diorama-esque living room in Cuba, embroidered with the words “POOR OLD PAPA”. There is no inkling I can find in the book or online as to how this somewhat self-pitying addition was made to the Papa moniker, but it struck me as telling. A clue as to how this all-conquering, 20th Century renaissance man actually saw himself. At least in his family.

Fatherhood can feel like a thankless task at times, no matter how invested in it or in love with their children one may be. Pity is always there for the tired father, feeling neglected by an exhausted wife and children who almost always instinctively seek her out first. Traditional masculinity doesn’t make a lot of room for humility and nurturing. There are battles to be won. Nurses shall see to the wounds. Discipline feels a lot more straightforward and safe a task than actual guidance, which asks for empathy or self-questioning.

When I was reaching manhood in the 1990s, all the cultural talk was of the Sensitive New Age Guy, or SNAG. Anyone who questioned old ideas of masculinity was quickly labeled a SNAG, with half a sneer. Myself included. I don’t recall getting any answers to those questions from the sneerers. “Sensitive” just felt like code for touchy or weak — it still does — and fatherhood only raised more questions about masculinity for me, which old models couldn’t answer. About how discipline relates to self-doubt. Fun to boundaries. Exhaustion to pity.

The Hemingway documentary painted a rather harrowing picture of a man not so much raised-up by his unbridled, pre-SNAG, fully-realized traditional masculinity and tremendous literary success. But rather, beaten down by the unrealistic ledger of expectations he put before himself. Especially as he grew older. Drinking Bellinis all night, after a long day fishing for a catch twice the size of you, then squeezing out a few pages; or dashing into wars you’re not part of, notebook in hand; or remarrying every time things get wobbly, while still rising every dawn to man the typewriter, doesn’t age well. Nor does it make you a better husband and parent.

To me Ernest looked much less like a vivacious raconteur, chasing adventure; than a scared boy running away. A portrait of weakness, spun during that cultural moment to look like strength. I sense he felt it, too. That he had to present a certain way, to survive the era and thrive in the market place.

It’s certainly not something to aspire to. Hemingway was the name my mother had, and after becoming estranged from my own father in my late-twenties, a much more comfortable choice to go by. But I hope people don’t confuse my name with my aspirations as a writer, husband or father. Those roles are just a set of likely coincidences between Ernest and I.

Every now and then, when a person gleefully asks me “Any relation?” I reply, Not that I’m aware of. More often than not the stranger looks a little disappointed. In which case I will add, No raging alcoholics or suicides in the family either… Which tends to snuff out the banter quite nicely. I might now continue; I’m also a pretty reliable husband and father.

I learned plenty from Ernest’s economy of style as a keen young writer, but haven’t reentered his world in some time. It’s been four years since I watched the documentary and these days my shoulder feels just about as good as new. I no longer test it with games of pick-up basketball (the second dislocation), and try to be mindful that my body is in general less and less robust. I am fast becoming the Old Man. The Sea, I can report, is still the rollocking sea.

But I can play sports with the kids, help passengers with their overhead luggage, load things in and out of the attic or the car, and all the other usual jobs.

It’s a good thing, too. My shoulders aren’t perfect, yet still the human body’s most versatile joint. One I appreciate more than ever. Their dexterity is unmatched by other muscle groups. They carry a lot of weight, but not without limits. Regularly called upon to perform all sorts of tasks, at various angles, with a never-ending range of specific strengths.

Kind of like a father.

Ernest's public persona was eventually revealed for what it was - a fraud. He had known all along that his image and reality didn't come anywhere close and I think that's why he obliterated it all with alcohol and finally suicided. A great read as usual.