Blood On The Diamond

Who said sport was meant to be fun?

Listen to the story, read by me. If you prefer…

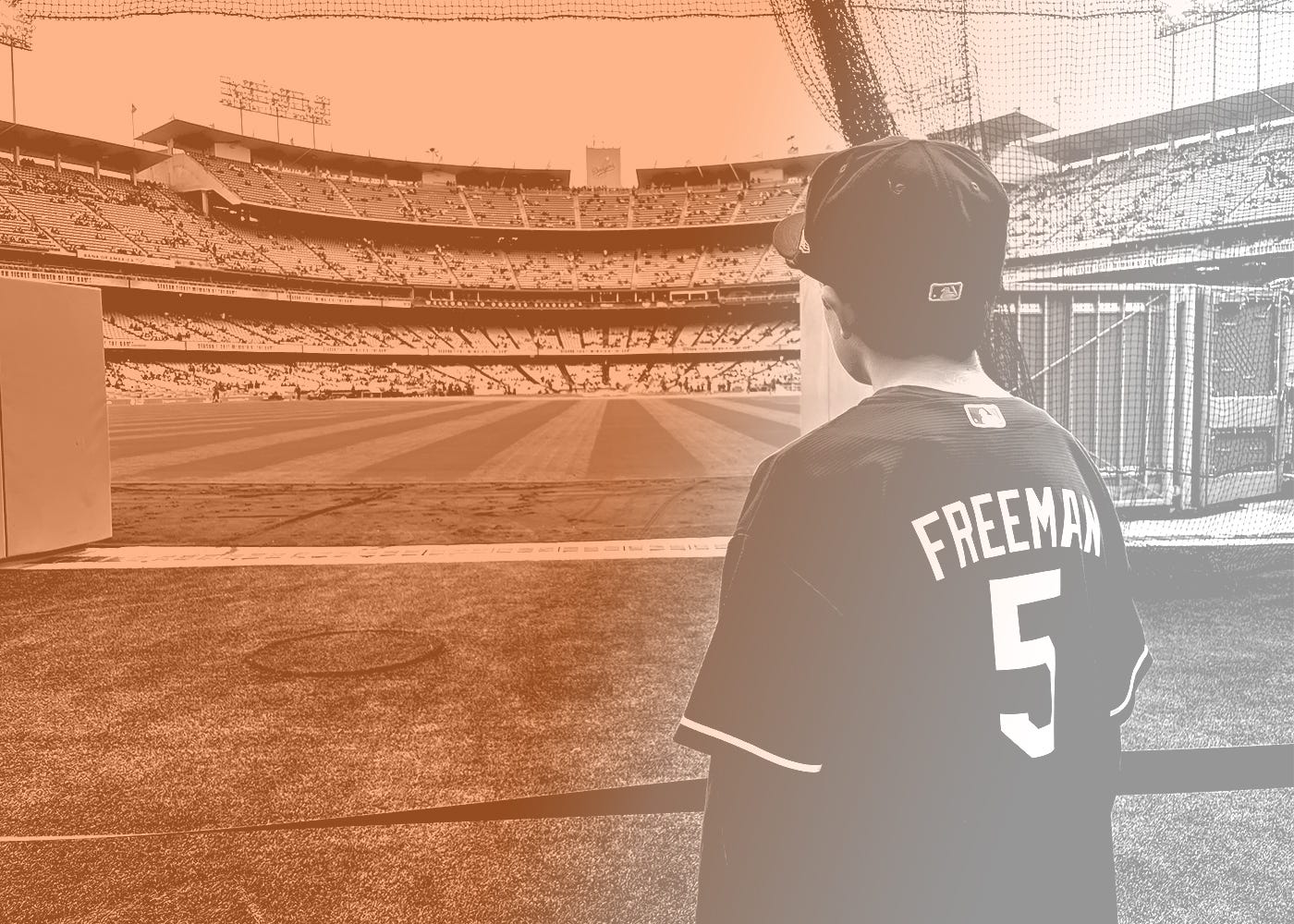

My son’s baseball team sucks. It’s true. He’d tell you the same. It’s no one’s fault, particularly, things just haven’t clicked. As the Little League Minors regular season drew to a close this year, I feared they might come unstuck completely.

Out on the field before the team’s second-last game, my son didn’t look worried though. Narrow and long limbed, he hurled the ball with the ease of a veteran darts player three pints in. Then caught the return throw in his cherished glove and moved it back to his right hand seamlessly, as if swiping washing off a line. I would have killed for those moves at his age.

The team’s field sits atop a surprisingly bucolic hill for central Los Angeles, at the intersection of numerous walking trails, overlooking the city’s west. (A repurposed municipal dump, I was once told.) Fat palm trees surround it where light towers might otherwise stand. My son and his teammates were throwing and catching far beneath them, in the low sun. They ran through swathes of blooming white clover, blanketing the outfield grass, to collect errant throws or missed catches. Of which there are always plenty with this mob.

It was a fitting scene for a sport often called America’s Pastime. A national right of spring. Inseparable from the optimism inherent in the country’s founding, as well as the time of year it is traditionally played. So, despite the team’s horrid midseason slump, hope was in the warm, early-evening air.

Then the game began, and like a crudely constructed billy cart barreling down a too-steep hill, everything fell apart. Afterward, my son picked himself up and carried home another loss to dissect at dinner.

I don’t know what I expected from the junior leagues when my son first showed interest in sport. I love sports, but was never a dad who dreamed of his son or daughter becoming sporty. I’ve waited eagerly to see their passions sprout, while trying not to be too invested in what those might be.

My son was drawn to the rolling ball always. Jumping into pee-wee sports clinics across codes and fiercely dunking anything that would fit through his mini basketball hoop from the moment he could stand.

Watching little kids chase runaway balls in oversized uniforms was cute then. I expected error ridden calamities masquerading as games. But my son wears deodorant now. There is nothing cute about 11-year-old boys working up a pungent sweat. I want new skills. Close calls. The joys of victory. All of a sudden, I want results.

After multiple seasons, rounds of gear in escalating sizes bought and lost, hours and hours of driving him to practices and games, talking him through the highs and lows, watching him improve so much, so earnestly… I feel a little invested. His passion for play and competition is blurring with my history as a sports tragic. I struggle to sit down during his games, pacing the fence, avoiding chit-chat. This is a form of torture I was not prepared for as a parent. Or a sports fan. He hasn’t even tried out for a middle school team yet.

For my son’s final regular season baseball game of the year they were on the big field. There are light towers there, should the innings go long, and the scoreboard works. Which are both a real treat if you’re winning. But this team doesn’t do a lot of that, and this game was no exception. Until then, I didn’t even know a Little League scoreboard could go into the 20s.

When the lights did eventually come on, my heart only sank deeper into darkness. His little sister was with me, and calling it all off on account of low light was our family’s only shot at both a reasonable bedtime and sweet mercy.

Instead the opposition batters basked gleefully in the towers’ tungsten glow. Close your eyes and you could have thought you were at a driving range, as ball after ball pinged off swinging tin. It was a bloodbath.

In accordance with Minor Little League rules, early innings were restricted to a maximum of four runs per team. But the last inning was “open”, no cap, a provision that allows for big comebacks. Or in the case of this game; promises false hope.

Opposition batters hammered loopy pitches from rookie arms, of which my son’s team has a seemingly endless brigade. Returning to the plate multiple times, as the batting lineup turned over, and the runs poured on.

There was no ump, he never showed. So coaches took turns standing safely behind the pitcher’s mound – avoiding the wild pitches slamming into the wooden barrier behind home plate – making distant, guesswork calls. One very suspect third-strike ruling on a teammate brought my son to near-tears. I couldn’t blame him. He was trying his heart out, they all were.

I try to be a reliable fan, and keep up the positive talk for good efforts, regardless of the score. Some parents cheer, some don’t say a word, yet the worst encourage sloppy play. “Good job, Timmy!” they yell, as the ball rolls beneath a barely-extended glove. These parents find a place in the darkest part of my heart, largely reserved for drivers who don’t use turn signals and bartenders that short-pour beers.

The kids save their ire for the umps. But whether it’s a coach doing his best from the wrong end of the diamond, or a paid official, I hardly notice the difference in quality. Official Little League umps are a curious bunch, seemingly drawn from two distant generations: Pimply teens and grizzled veterans. Most bad calls (of which there are plenty) are due to either youthful inexperience or decades of alcoholism, if you ask me.

At my son’s previous game – when hope still lingered – “Blue” (as umpires are most often called, on account of their shirt) was of the grizzled persuasion. The teens will sometimes wear shorts and few pads, ready to simply hop out of the way of wild pitches. The more experienced umps, like this Blue, take no such chance. He clomped across the diamond in full face, chest, leg and foot armor. Most of it concealed beneath wide waiter’s slacks, Frankenstein-black shoes to match, and the traditional powder-blue polo. He could barely move.

Yet each time he called a strikeout – from a strike zone that appeared, to my naked eye, so varied from pitch to pitch as to be mathematically impossible – Blue performed a cute, spritely shimmy, pumping his hands back and forth in the air. Like he enjoyed sending those traumatized little batters back to a cage full of resentful peers. It was hard to watch.

Though, in truth, such characters are in large part what makes youth sports so beguiling to me. Every team my son has been on is chock full of perfect dramatic types. Sporting teams are like the cast of an old war movie that way. You have your Hotshots, your Loudmouths. The Quiet Guy, the Bookworm, the Loner. The Tough Guy (with a heart of gold). The Surprise Packet. The Big Guy… and so on.

The Little Guy on this team is the Coach’s kid. In a war movie, he’d be the one who dies tragically during the first act, inadvertently propelling the rest of the action. In this game, he came frighteningly close. It just wasn’t enough to unite the troops for a comeback win, sadly.

Top of the second inning, the Little Guy was rescued from his usual outfield marooning, and placed at second base. A routine hit headed his way, took one unpredictable bounce, hopped over his glove and smacked him clean in the face. The game stopped. He was hurting.

A kind of shared, hormonal, emergency response ran through the parents in the bleachers. Each of us trying to do something to help. Before settling back into that familiar old feeling of sheer helplessness, that begins beside the crib.

One of the other dads is a doctor. Straight from work and still in his scrubs, he calmly made his way over to the dugout, took one look, and knew just as much as we all knew. No medical degree required. Poor kid's nose was busted, right across his face. Ice packs were hurriedly obtained and applied. A grandad gave up his folding chair. Finally Coach reverted back to being Dad, taking his son to the emergency room. Like I said, it was a bloodbath.

The runs piled on from there. The final, “open” inning felt endless, stuck at only one out. The team pizzas went cold. I was already running late to meet a visiting friend for a drink, and had never needed one more.

I won and lost countless sporting games as a kid, but don’t recall feeling nearly as tormented as I do now, on a Wednesday evening, nearly fifty-years-old, mulling over the volunteer coaches’ decisions, riding every fielding error and wild pitch, with absolutely nothing on the line. This is why I don’t gamble.

Eventually my son was brought in to pitch, and try to end the chaos. I love to see him pitch. It gives me a false sense that I’m somehow biologically in control of the game’s outcome. But heck, I can’t throw like that. Never could. As he approached the mound his friends on the opposing team murmured his name through the dugout, with quiet reverence.

He gave up one more run off the loaded bases he’d inherited, before cheerily striking out their last two batters, including their Big Slugger. Then he carefully set down the ball on the mound and hopped over to the dugout. The coaches relaxed their shoulders, the parents took a breath. I unclenched my hands from around the contours of the 20-foot-high chainlink fence. A kind of calm fell over the battlefield.

Not an easy one, though. No word from the hospital, and we haven’t even started the playoffs.

Wonderful piece Toby. We had a football team member whose father came to every game we ever played. He would be there half an hour before the rest staggered in examining the ground, practicing moves and drills with his poor son who just wanted to be like the rest of us with no parental involvement whatsoever. Once the game started, he became a crazed animal, prowling the perimeters screaming instructions through foam saturated lips. At the end he had to have a lie down in his car before he even confronts his son with his list of unforced errors the poor lad had made. Memorable.